Y-DNA testing has only been around for about 15 years and can tell

us about our direct paternal ancestry.

It is sometimes criticized for only being able to tell us about a small

portion of our genetic history. I think

the critics forget that our mothers have fathers and there are a number of ways

to obtain male test subjects to expand Y results across the entire family

tree. In the last few years, there has

been a brighter spotlight on autosomal testing and its ability to test a larger

portion of our genes. This may have

diverted research attention. Relatively

speaking, y-DNA is still in its infancy and there is much more to be learned. In addition to our deep ancestral origins

dating back over 10,000 years, we should be able to identify our old world

homeland and our nomadic ancestor’s migration routes. It is meaningful to know not only where they

lived, but also when they lived to give us clues to their part in history.

My closest genetic cousins and I share a common

ancestor over 1,100 years ago. With that many years between us, I didn’t

spend a lot of time looking for a common surname. For the last four

years, I’ve been working with y-DNA to determine what can be learned beyond

cousin matches and distant origins. I originally tested with the

Genographic Project and then transferred my results to Family Tree DNA for an

upgrade. In the time since getting my upgrade to 67 markers, I have

received only one match. This is due to my haplotype being somewhat rare

and not a reflection of Family Tree DNA’s ability to provide matches. I learned

that I was part of haplogroup G, from the Caucasus Mountains. I

didn’t learn anything about how the ancestors of my Italian family traveled

from Western Asia to Italy.

I needed to find more cousin matches than the client

base that had tested with FTDNA. Ancestry.com allowed me to enter my

y-DNA markers into their DNA section. I compared my haplotype against the

database at Sorenson Molecular (SMGF.org). I also tried Genebase.com and

any other place I could find. I didn’t locate any cousins. I did

get a good education on what is out there for DNA companies and services.

FTDNA allowed me to transfer my results to Ysearch.org, a free public DNA

matching service that they provide. Ysearch provided much more

flexibility. Where FTDNA would only show me matches with a genetic

distance of seven or less, Ysearch allowed me to select the genetic distance.

Without the genetic distance restrictions, Ysearch showed me hundreds of very

distantly related cousins. I’d rather have distant than none. FTDNA

is not trying to be difficult. They are trying to be realistic and keep

matches within genealogical timeframes. I just needed more.

While not used consistently, one of the best features

of Ysearch is its ability to present the most distant known paternal ancestor

(MDKPA) and their origin. So now, I had cousins and their ancestral

origins. The greater the genetic distance, the closer I got to the

Caucasus Mountains. I mapped my closest cousins and their pushpins

created a line from the Alps to the North Sea, directly along the Rhine River.

This was a pattern. I like patterns. There is usually a

scientific reason for a pattern.

Figure 1 – Mapping Ancestral Origins

I’ve run a few hundred

genetic mapping exercises on the majority of Y haplogroups. The patterns are consistent. Our ancestors traveled along rivers and

coastlines. They skirted mountain ranges

and crossed bodies of water. There is

always a flow to the patterns, but the science and the why were still missing. I’ve always been interested in early Eurasian

history and have tried to associate it to the patterns in the maps that I

generated. Some maps have places and

dates that connect well to notable events.

Other maps raise more questions than answers. Genetic tests and history alone were not

making a complete picture. I needed to

add population genetics, migration models, anthropology and evolutionary

biology to my knowledge base.

Take any two people on the planet, compare their DNA and you can

calculate, approximately, how far back in time their common ancestor lived –

time to most recent common ancestor (TMRCA).

Our ancestors were nomadic and traveled about 25 to 30 km per generation

or roughly 1 km/year on average. If a

common ancestor lived 300 years ago, then that person’s descendants may have

migrated 300 km from the geographic origin of that ancestor. In the figure below, d1 and d2

represent the origins of two known y-DNA genetic records. The circles show the distance their ancestors

may have migrated. The intersections are

the potential locations of their common ancestor. In this case, there are two intersections, a1

and a2. More y-DNA records

are required to figure out which intersection is correct.

Figure 2 – Distance to Most Recent Common Ancestor

(Bilateration)

The genetic analysis that

I have developed is similar to a navigation technique. Radio navigation uses two or more beacons

with known locations and a measurement of the time it takes to receive a signal

from each. The time is converted to a

distance. A current location can then be

identified. In my method, the “beacons”

are the ancestral geographic origins. The

“signal” is the TMRCA, measured in years, converted to a distance by

multiplying the average migration rate – creating a distance to most recent

common ancestor (DMRCA). A location for

the common ancestor can then be figured out by looking at the intersections. Multiple y-DNA records are needed to

determine migration direction and geographic origins of a related set of

genetic cousins. The science is starting

to take shape.

I am G-Z726, which is a subgroup of G-Z725. At Ysearch or on an FTDNA project you may still see an older naming convention - G2a3b. As an example, let’s look

at 18 of my closest genetic cousins – haplogroup G-Z725, (DYS388=13). TMRCA data is generated using Dean McGee’s

Y-Utility. The output is turned into a

phylogenetic tree and the DMRCA is calculated.

Figure 3 - Phylogenetic Tree - G-Z725 Sample

Each distance is used to draw a circle that represents the

migration range of that ancestral line.

My range (MAG) and the range of my next closest cousin on the tree (BAB)

create two intersections on the map. One

point is in Africa and

Figure 4 - Intersection of MAG and BAB

By adding the range of cousin EBE, the correct intersection representing

common ancestor 7 (CA7) is identified.

Pairs of records are mapped to continue the analysis.

Figure 5 - Intersection of BIR and RUF

BIR and RUF are another example and they identify common ancestor

CA3. Each record is added until all

common ancestors are identified.

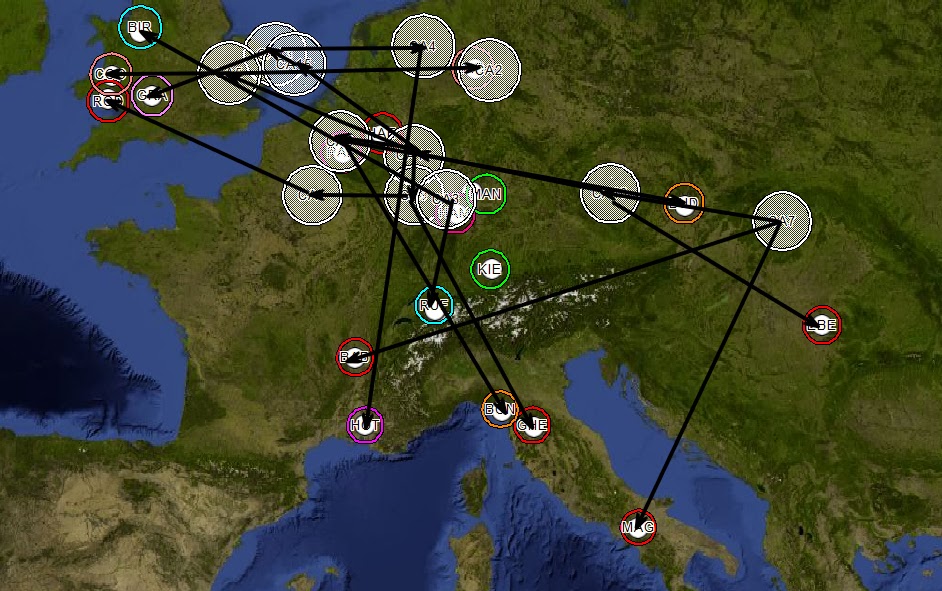

Figure 6 - Common Ancestors Mapped

Connections are drawn based on the phylogenetic tree.

Figure 7 - Phylogenetic Tree Superimposed

Then for simplification, the migration flow is generalized. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, common

ancestor 7 (CA7) is the most distant common ancestor (MDCA) of samples in this

example. The western migration flow has

a slight correlation to the Danube River and the North/South migrations have a

strong correlation to the Rhine River.

Early attempts at direct mapping of genetic data (Fig. 1) gave similar

results based on TMRCA alone. There was

no corroborating

Figure 8 - Generalized Migration Flow - G-Z725

The new methodology that I have developed

shows ancestral origins and migration direction. I call this method biogeographical

multilateration (BGM). It is the

geographical distribution of y-DNA data based on multiple distance measurements

from reference positions.

This method also has the

potential to identify the location of a DNA sample when the origin is unknown. For

one of my clients, I identified that his paternal ancestor that had immigrated

to the United States may have anglicized their name. The previous name was German and that surname

was found predominantly in central Germany.

Applying biogeographical multilateration to my client’s y-DNA results,

while leaving the origin as an unknown, indicated a continental European origin

within 200km of the city with the highest surname density.

In the referenced paper,

the example haplogroup, I-L22, has an approximate correlation to the

Norse/Viking invasions of Britain and identifies a Frisian coast staging area.

Figure 9 - Generalized Migration Flow - I-L22

We are still in the

infancy of what we can learn from y-DNA.

My BGM analysis has room for refinement.

There is enough science out there to help us. New research is being done at the aggregate

population level. We can apply elements

of that research to the individual level.

Biogeographical multilateration has the potential to fill the gap in our

knowledge between genealogical records and deep haplogroup roots. This new tool can give us old world ancestral

origins, migration flow and historical timeframes.

I needed to learn more

about my DNA and my origins. The big

testing companies haven’t filled the knowledge gaps that exist. They are in the business of providing quality

test results. The analysis and tool

creation is falling on the shoulders of “citizen scientists”. Sometimes, you just have to do it yourself.

Reference:

Maglio, MR (2014) Y-Chromosome

Haplotype Origins via Biogeographical Multilateration (Link)